By DAVE VOGEL | Wauwatosa Historical Society

Zeddie Quitman Hyler built the frame for his 113th Street ranch house in 1955, came back the next day and discovered vandals had damaged it. Hyler repaired it, but vandals returned, this time setting the frame ablaze. Clearly, some Wauwatosans didn’t want the African- American postal clerk as a neighbor.

Hyler reported the vandalism to the police, said Hyler’s nephew, Gerald Williamson. “But nothing ever came of it.” All that remained of the house was the concrete basement. Anticipating a third attack on the property, Williamson said, Hyler enlisted the help of his brothers and some friends. About nine of them, armed with hunting rifles, spent a night in the open basement, braced for a battle that never came.

Years later, Williamson said, Hyler looked back on “the Ponderosa” night, a scene right out of the Wild West. Destruction of the frames were among the last of Hyler’s physical hurdles. While painting the house, someone with a slingshot fired a rock at him. The rock missed, but damaged a window casing.

Hyler also put up with about 75 threatening phone calls. “Stay where you belong,” one caller warned Hyler. “It didn’t scare me,” Hyler told the Milwaukee Journal in a 1987 interview. “My thoughts were that I had a right to live here and I planned to live and die in this house.”

Hyler was born in 1918 in New Albany, Miss., one of 10 children of a sharecropper. He ran away from home so he could attend high school. His father wanted him to stay and work on the farm, Williamson said.

Hyler worked his way through college, earning a bachelor’s degree in vocational education from Alcorn Agricultural and Mechanical College in Alcorn, Miss.

Hyler served in the Army during World War II and moved to Milwaukee about 1950, Williamson said.

Hyler served in the Army during World War II and moved to Milwaukee about 1950, Williamson said.

“I just wanted a good life for myself and my family,” Hyler told the Journal in 1987.

Before moving to Wauwatosa, Hyler lived at 2363 N. 9th St. in Milwaukee. Hyler was part of a huge northward migration of blacks in the years after the war. Between 1940 and 1960, Wisconsin’s black population increased by nearly 600%, according to the Wisconsin Historical Society.

Most of the newcomers settled in urban areas, resulting in so-called chocolate cities surrounded by vanilla suburbs. Whitefish Bay was sometimes mocked as “White Folk’s Bay;” Wauwatosa was “White-a-tosa.”

Today, Wauwatosa is 87.4% white and 4.5% black. Minority enrollment in Wauwatosa’s public schools is more than 30%, Wauwatosa NOW reported last January. The nation’s first black president, Barack Obama, carried Wauwatosa in both the 2008 and 2012 elections.

It was a different world in 1955. Hyler asked a white friend to buy the property and then sell it to him, figuring no real estate agent would sell a Wauwatosa lot to a black man, Williamson said. As the first black to build in Wauwatosa, Hyler was a pioneer with prominence.

His application for a building permit earned him a front-page headline in the Wauwatosa News-Times. “I went right to City Hall and applied for all of the permits in person so they wouldn’t have to guess who was coming to dinner,” Hyler told the Journal.

A two-member committee had rejected the application because of neighbors’ objections. Rudolph Lehn, a bricklayer who lived two blocks south of Hyler’s property, said at a public meeting that he feared his property would be devalued if Hyler moved in.

Others, including church groups, citizen groups and representatives of the YWCA expressed outrage over the treatment of Hyler. The building board overturned the committee’s decision at a meeting in February 1955. Hyler attended the meeting, but sat silent.

“I went right to City Hall and applied for all of the permits in person so they wouldn’t have to guess who was coming to dinner,” Hyler told the Journal.

Afterward, several people came forward commenting “that hurdle is passed.” But the city council then imposed a 30-day ban on all permits in Hyler’s neighborhood, noting that planners were still determining the path of the freeway to be built north of North Avenue.

Once the freeway plan was announced, Hyler was granted his permits. “Negro’s Home Plan Okayed,” a Journal headline read.

Hyler and his brothers finished building the house, and he and his then wife Mary and their son, Butch, soon moved in. “For sale” signs soon popped up in the neighborhood, the Milwaukee Sentinel reported years later. But the sudden sales surge also may have coincided with the freeway project. Hyler’s home directly faces the southbound lanes of I-41/U.S. 45.

About one month after the building committee meeting, the News-Times carried a page-one headline that read: “Negro Physician Applies for Bldg. Permit This Week.” The physician, Arthur Sanders, built a home on Park Ridge Ave. That development apparently attracted no controversy.

While living in Wauwatosa, Hyler continued working for the postal service and also owned several rental properties in Milwaukee. He was a board member of the North Central YMCA and active in several organizations, including the Masons.

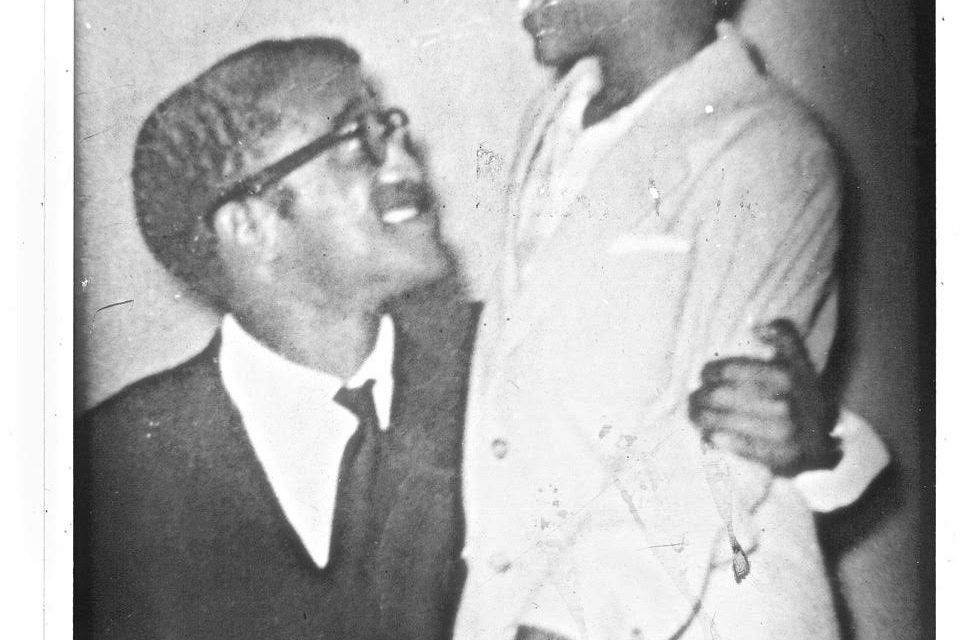

Hyler also loved entertaining, Williamson said. Among his guests on 113th Street were entertainer Sammy Davis Jr. and baseball great Hank Aaron, he said. Hyler and Davis served together in the Army during Word War II, and Davis visited the Hyler family while performing in Milwaukee. He was photographed embracing Hyler’s son, Butch. Butch died in his mid-20s, Williamson said. Hyler probably knew Aaron through his involvement with the Masons, Williamson speculated.

After the initial hostility, Hyler lived with his neighbors quietly and peacefully for the next 49 years. He died Dec. 30, 2004 at age 86.

“I think they realized I was coming to stay, and that was pretty much the end of it,” Hyler said in the Journal’s 1987 interview.

Williamson, who now owns the 113th Street house, is seeking some sort of official recognition of the history of the property. If nothing else, he may place a memorial plaque on a tree in front of the house.

Williamson noted that his own father had abandoned him when he was born and that Hyler had taken him under his wing and mentored him. Williamson. “I want to honor him,” he said. “He was a good man.”

This article first appeared last November in Historic Wauwatosa, published by the Wauwatosa Historical Society. For information about joining, go to wauwatosahistoricalsociety.org.