Pioneer widow journeyed more than 1,000 miles to become a Tosan

By Dave Vogel

With all her worldly possessions tightly packed into a covered wagon from Massachusetts to Wisconsin. On the Fourth of July 1844, she arrived at what would be her home for the remaining 43 years of her life, Wauwatosa.

Her father fought in the American Revolution, and she was born in the last year of George Washington’s presidency, so it’s understandable why the Wauwatosa chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution chose her as its namesake, said Barb Benton, historian for the DAR chapter.

It’s also understandable why the guest list for the plucky pioneer’s 80th birthday party reads like a Wauwatosa Who’s Who of the era.

Hill was born in Enfield, Conn., on April 13,1796. She was the seventh of 11 children born to Jonathan Avery and Pamela Fox Avery. Avery was a Revolutionary War veteran who had served in the 10th Continental Infantry during some early and disastrous defeats.

On Dec. 25,1815, Annis Avery and Caleb Hill of Gardner, Mass., were married. She was 19 and he was 29. Caleb was a blacksmith, mason and farmer. They had eight children. When Caleb died in 1842, the youngest of their children was 5 years old.

Their eldest daughter, Adaline, was 24. At age 15, she had married Thomas M. Riddle, who had settled in Wauwatosa in November 1835, the first year settlers came to Wauwatosa. Riddle was a longtime owner of the Little Red Store.

Two years later, Annis Avery Hill and her remaining children took off for Wauwatosa to join Adaline. The trials of that overland journey are unknown, so we can only imagine the help she received from her oldest sons, the provisions they carried, the miles they traveled, the rivers they crossed, and the hardships they endured.

Through the next four decades of her life, Annis Avery Hill taught Sunday School at the Congregational Church, cooked, made quilts and rugs, and established many friendships. And to her friends and family, the woman who always wore a white lace cap was known as Grandmother Hill.

Through the next four decades of her life, Annis Avery Hill taught Sunday School at the Congregational Church, cooked, made quilts and rugs, and established many friendships. And to her friends and family, the woman who always wore a white lace cap was known as Grandmother Hill.

The children she reared and her 21 grandchildren scattered across the nation. One son, Homer, was a captain on the Great Lakes. Her youngest son, Dexter, served in the First Wisconsin Cavalry during the Civil War and later was a Congregational minister in Los Angeles. A grandson, Charles Hill, was a Naval Academy graduate who was awarded a gold sword from the Brazilian government for his instrumental role in suppressing a rebellion. Another grandson, Warren B. Hill, was president of the Children’s Home and Aid Society and dean of the Milwaukee Medical School. Another grandson, George Hill, was mayor of Antigo.

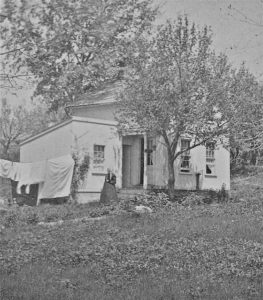

For her 80th birthday, friends and family celebrated at what certainly was an alcohol-free party. It was held at the Good Templars Hall, adjacent to Grandmother Hill’s home on Mower Court. Temperance crusaders had built the lodge in 1874 and used it for nearly three decades. The building now is used as a residence.

“Among the guests,” according to Gloria Rockwood Houghton, a great-great-granddaughter of Annis, “were Mr. and Mrs. James Stickney, Mr. and Mrs. L.B. Porter, Mr. and Mrs. J.M. Warren, Mr. and Mrs. Lowell Damon, Mr. and Mrs. A.B. Mower, Mr. and Mrs. E.S. Earls, Mr. and Mrs. Charles Jacobs and Mr. and Mrs. Edward Caldwell.” Stickney, Potter, Warren and Mower probably are most recognized today as mere street names.

On display at the party was linen that Grandmother Hill had spun 61 years earlier for her wedding dress, as well as a rug she had finished making a few days earlier. Her pastor for many years, the Rev. Luther Clapp of the Congregational Church, spoke of her zeal and faithfulness in the church. Deacon L.B. Potter spoke of her work with the Sunday School. And the Rev. Enoch Underwood, pastor of the Baptist Church, spoke of the scientific discoveries and inventions during Grandmother Hill’s 80 years.

Nine years later, Grandmother Hill died and was buried at Wauwatosa Cemetery. Under a small headline that read “Almost 90 years old,” her death was reported in a two-sentence notice in the Milwaukee Sentinel of May 26, 1885: “Mrs. Annis Hill died at Wauwatosa yesterday, aged 89. She will be buried tomorrow at 3 o’clock.”

years old,” her death was reported in a two-sentence notice in the Milwaukee Sentinel of May 26, 1885: “Mrs. Annis Hill died at Wauwatosa yesterday, aged 89. She will be buried tomorrow at 3 o’clock.”

In addition to being the namesake of the DAR chapter in Wauwatosa since 1954, Annis Avery Hill is memorialized on a historical marker at Wauwatosa Cemetery. The Wisconsin Society of the Sons of the American Revolution placed the marker there in 2006. Its plaque notes that Hill is buried at the cemetery along with James Morgan, a veteran of the war who settled in Wauwatosa in the 1830s, and Lyman Wheeler, whose grandfather was an eighth-generation American who fought at Lexington.

A Birthday Dream

Below is an excerpt of a letter to Annis Avery Hill from her daughter, Adaline A. Riddle, on the occasion of Hill’s birthday. At the time she wrote the letter, Adaline was 55 and had been a widow for 17 years. She was living in Appleton so she could be closer to the youngest two of her five children, who were enrolled at what today is Lawrence University.

Appleton, April 11, 1876

Dear Mother,

I am sorry that I cannot be present at your party but it will be impossible as I explained to you in my last letter. Therefore, please accept my regrets; perhaps the only contribution I can make to the entertainment will be to relate a dream I had. One night I was thinking of your proposed celebration and sighing over hard times, scarcity of money and miseries of widows in general, when I fell asleep and dreamed that the Chicago Northwestern Railroad advertised to run a special train free to your birthday party! I seized the opportunity of course and rushed on board with the throng. We were soon flying along the track and, directly, we passed freight cars loading from a huge gray pile which they told us was the flax and tow you, had spun and woven since you were just a girl — it was to be taken to the party. Farther on, we passed another miniature mountain, white and fleecy, the wool you had spun. Freight cars were loading that too, to take to your party. Next, we saw clothing of all kinds hanging from the telegraph wires, boys’ clothes, girls’ clothes, clothes for women and for men — all ticketed for your celebration. These were the clothes you had made. But on we sped, stopping to take on passengers at the stations. At one place, they had a glass case to send, filledwith white lace caps — not a black one among them. We waited a moment longer while they loaded several mail bags which thy said contained the letters you had written and the Sabbath school papers you had given to children. The conductor shouted all-aboard and we were again flying through the country. We slackened on the side track where they coupled on a car loaded with rags, rag carpets and patchwork quilts. Again, we rushed ahead. Soon we approached a large depot where we passed long tables loaded with food they said represented the cooking you had done. There were many children here too and they all had “turnovers” in their hands. They scrambled on board and as we moved on, we were accompanied by countless birds filling the air with music. They were singing lullabies, and Sunday School songs, and hymns, and just ordinary wash day songs. As we went along, a lady remarked that she didn’t see how any one could do so much. I said, ‘Madam, she was born when Washington was president of the United States! Behold, how great is the aggregate of eighty years of industry.’ And the children stood up and repeated in concert: ‘Every man shall receive his own reward according to his own labor; blessed are the dead who die in the Lord for they shall rest from their labor and their works do follow them!

Yours affectionately,

Adaline A. Riddle

This article first appeared in Historic Wauwatosa, published by the Wauwatosa Historical Society. For information about joining, go to wauwatosahistoricalsociety.org.